Here you can find a listing of multiple studies that summarize findings about C. difficile infections and the effectiveness of natural therapeutics.

Here you can find a listing of multiple studies that summarize findings about C. difficile infections and the effectiveness of natural therapeutics.

While this is not an all-inclusive study listing, this should give you hope when it comes to the many natural options available for treating C. difficile. Also included are numerous probiotic and Bacillus spore probiotic studies and their health benefits.

You can click these links to skip to the following sections:

Antibacterial Remedies for C. diff.

Probiotics and S. boulardii for C. diff.

Bacillus Spore Probiotics for C. diff. and Other Gut Challenges

Antibacterial Remedies for C. diff.

Many natural antibiotics exist that have tremendous activity against bacteria, viruses, yeasts and parasites. Below is a listing of some data that Michelle has pulled together regarding C. diff and natural herbal extracts.

Published Laboratory Tests using Non-Antibiotic Agents Against C. difficile Bacteria

- Anaerobe. 2022 Aug:76:102604. In vitro anti-clostridial action and potential of the spice herbs essential oils to prevent biofilm formation of hypervirulent Clostridioides difficile strains isolated from hospitalized patients with CDI. Ana Aleksić, Zorica Stojanović-Radić, Celine Harmanus, Ed J Kuijper, Predrag Stojanović

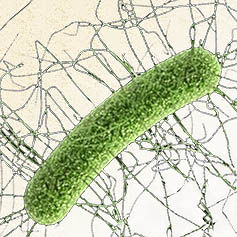

Abstract: Clostridioides difficile is the most common causative agent of antibiotic-acquired diarrhea in hospitalized patients associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. The global epidemic of CDI (Clostridioides difficile infection) began in the early 20th century with the emergence of the hypervirulent and resistant ribotype 027 strains, and requires an urgent search for new therapeutic agents.Objective: The aim of this study is to investigate the antibacterial activity of the three essential oils isolated from spice herbs (wild oregano, garlic and black pepper) against C. difficile clinical isolates belonging to 6 different PCR ribotypes and their potential inhibitory effect on the biofilm production in in vitro conditions.

Conclusion: Essential oils of wild oregano, black pepper and garlic are candidates for adjunctive therapeutics in the treatment of CDI. Oregano oil should certainly be preferred due to the lack of selectivity of action in relation to the ribotype, the strength of the produced biofilm and/or antibiotic-susceptibility patterns.

- Letters in Applied Microbiology, Volume 75, Issue 3, 1 September 2022, Pages 598–606. Antibacterial and antibiofilm activities of some plant essential oils and synergistic effects of cinnamon essential oil with vancomycin against Clostridioides difficile: in vitro study. M.N. Tosun, G. Taylan, N.N. Demirel Zorba.

https://academic.oup.com/lambio/article-abstract/75/3/598/6989339

Abstract: The detection of resistant strains of Clostridioides difficile against existing antibiotics and the side effects led to the investigation of alternative agents. Inhibition zones of various essential oils to four strains of C. difficile and other Clostridium species ranged from 8·32 to 44·18 mm. The highest zone was observed in cinnamon and tea tree essential oils. and The MIC values varied between 0·39–25 (%, v/v). The main components were cinnamaldehyde (85·64%) in cinnamon essential oil, 4‐terpineol (83·6%) was determined in tea tree essential oil. Additive effects were found between cinnamon essential oil and vancomycin and between cinnamon and tea tree essential oils, and the FICI values were 0·512 and 0·517, respectively. Both cinnamon and tea tree essential oils showed antibiofilm activities against all tested C. difficile strains at all tested concentrations. Essential oils may be used as a supplement in addition to treatment in the control of C. difficile‐related diseases. - J Food Sci. 2009 Oct;74(8):M467-71. Growth-inhibiting activities of phenethyl isothiocyanate and its derivatives against intestinal bacteria. Kim MG, Lee HS. Dept. of Bioenvironmental Chemistry, College of Agriculture & Life Sciences, Chonbuk Natl. Univ., Chonju 561-756, South Korea. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19799675

Abstract. The growth-inhibiting activities of Sinapis alba L. seed-derived materials were examined on the growth of Bifidobacterium bifidum, B. breve, B. longum, Clostridium difficile, C. perfringens, Escherichia coli, Lactobacillus acidophilus, and L. casei. The active component of S. alba seeds was purified using silica gel column chromatography and HPLC and was identified as phenethyl isothiocyanate by various spectroscopic analyses. The antimicrobial activity of phenethyl isothiocyanate varied according to the dose and bacterial strain tested. Phenethyl isothiocyanate strongly inhibited the growth of C. difficile and C. perfringens at 1 mg/disc, and weakly (+) inhibited its growth at 0.1 mg/disc. Furthermore, phenethyl isothiocyanate moderately (++) inhibited the growth of E. coli at a dose of 2 mg/disc, but did not inhibit the growth of bifidobacteria and lactobacilli. Addition of various functional groups to isothiocyanates resulted in selective inhibitory activity against harmful bacteria with low concentrations of aromatic isothiocyanates demonstrating greater inhibitory activity against clostridia and E. coli than aliphatic isothiocyanates. In conclusion, aromatic isothiocyanates containing phenethyl-, benzyl-, and benzoyl-groups might be useful in the development of novel preventive and therapeutic agents against diseases caused by harmful intestinal bacteria. - J Food Sci. 2007 Jan;72(1):S055-8. Trans-cinnamaldehyde from Cinnamomum zeylanicum bark essential oil reduces the clindamycin resistance of Clostridium difficile in vitro. Shahverdi AR, Monsef-Esfahani HR, Tavasoli F, Zaheri A, Mirjani R. Dept. of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology and Pharmaceutical Sciences Research Center, Faculty of Pharmacy, Tehran Univ. of Medical Sciences, 14174 Tehran, Iran. shahverd@sina.tums.ac.ir. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17995898

Abstract. Therapy with antimicrobial drugs, such as clindamycin, that perturb the intestinal flora but fail to inhibit growth of other microorganisms can permit the proliferation of Clostridium difficile and the elaboration of exotoxin. Therefore, there has been increasing interest in the use of inhibitors of antibiotic resistance for use in combination therapy. The essential oil of Cinnamomum zeylanicum bark enhanced the bactericidal activity of clindamycin and decreased the minimum inhibitory concentration of clindamycin required for a toxicogenic strain of C. difficile. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) analysis of the essential oil separated a fraction (R(f) = 0.54) that was the most effective at enhancing the clindamycin antimicrobial activity. Using gas liquid chromatography and known standards, the active fraction was identified as trans-cinnamaldehyde (3-phenyl-2-Propenal). Combinations of clindamycin and trans-cinnamaldehyde were tested to determine the fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index by conventional checkerboard titration. The FIC index for C. difficile was found to be 0.312, which confirmed the synergistic actions of clindamycin and trans-cinnamaldehyde. The presence of 20 microg/mL of trans-cinnamaldehyde decreased the MIC of clindamycin for C. difficile 16-fold, from 4.0 to 0.25 microg/mL. These results signify that low concentrations of trans-cinnamaldehyde elevate the antimicrobial action of clindamycin, suggesting a possible clinical benefit for utilizing these natural products for combination therapy against C. difficile.

Published Statuses of Current C. difficile Therapies

- Pharmacotherapy. 2010 Dec;30(12):1266-78. Alternative therapies for Clostridium difficile infections. Venuto C, Butler M, Ashley ED, Brown J. Department of Pharmacy Practice, The State University of New York, Buffalo, New York 14626, USA.

Abstract. Clostridium difficile infection is a serious condition responsible for significant morbidity and mortality, especially in patients being treated with antimicrobials. Increasing frequency of the infection and hypervirulent C. difficile strains have resulted in more severe disease as well as therapeutic failures with traditional treatment (metronidazole and vancomycin). To review the studies assessing nontraditional therapies for the prevention and treatment of primary or recurrent C. difficile infection, we conducted a literature search of the PubMed-MEDLINE databases (1984-2010). Of the 98 studies identified, 21 met our inclusion criteria. Five clinical trials and one retrospective medical record review evaluated probiotic or prebiotic formulations for the prevention of C. difficile infection. Only one of these studies, which included Lactobacillus casei and L. bulgaricus in the probiotic formulation, showed efficacy. Ten clinical trials evaluated treatment of an initial episode of C. difficile infection (primary treatment) with the anti-microbials fidaxomicin, fusidic acid, rifampin, teicoplanin, and nitazoxanide, as well as the toxin-binding polymer, tolevamer. Only nitazoxanide and teicoplanin demonstrated noninferiority when compared with vancomycin or metronidazole. Four prospective studies and one retrospective study evaluated treatment of relapsing C. difficile infection. Prebiotic formulations for the prevention and treatment of recurrent C. difficile infection have not proved to be clinically warranted. Nitazoxanide, teicoplanin, and fidaxomicin may be considered as alternatives to traditional treatment; however, clinical experience is limited with these agents for this indication. Bacteriotherapy with fecal instillation has demonstrated high clinical cure rates in case studies and in a retrospective study; however, to our knowledge, randomized clinical trials are lacking for this therapeutic approach. As C. difficile infection rates continue to increase and hypervirulent strains continue to emerge, it is important for future clinical studies to assess alternative therapies. - Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009 Mar;33 Suppl 1:S51-6. Alternative strategies for Clostridium difficile infection. Bauer MP, van Dissel JT. Department of Infectious Diseases, Leiden University Medical Center, 2300 RC Leiden, The Netherlands.

Abstract. Although antibiotics are generally effective in achieving symptomatic recovery from Clostridium difficile infection, the disease frequently relapses, partly because antibiotics not only kill C. difficile, but also disrupt colonisation resistance of the gut microflora. Non-antibiotic strategies for the prevention and treatment of the infection include probiotics, deliberate colonisation by non-toxigenic C. difficile strains, toxin-binding agents, active immunisation, passive immunotherapy with intravenous immunoglobulin, monoclonal antibodies or bovine anti-C. difficile whey concentrate, and faecal transplantation. None of these alternative therapies has proven benefit in therapy or prevention, and prospective randomised trials are urgently needed. - Age Ageing. 2008 Jan;37(1):14-8. Epub 2007 Nov 22. Clostridium difficile-associated disease: update and focus on non-antibiotic strategies. Thompson I. Department of Clinical Gerontology, King’s College Hospital, London SE5 9RS, UK. joscyn@hotmail.com

Abstract. Clostridium difficile-associated disease (CDAD) is a problem of especially the frail elderly. Changes in virulence of prevalent strains in the early years of the new century saw mortality and morbidity increase from historical levels. This article explores non-antibiotic strategies including the use of probiotics. A number of avenues of ongoing research appear to have potential future clinical application. Evidence exists linking acid-inhibiting drugs to an increased risk of CDAD, and the adjunctive use of Saccharomyces boulardii and infection control measures in the treatment of CDAD.Summary. In clinical practice infection control measures and S. boulardii remain the only clearly beneficial evidence-based adjuncts to antibiotic therapy of CDAD.Outside clinical trials, it is the author’s opinion that only oral S. boulardii should be used as an adjunct to the treatment of CDAD, although many institutions informally employ a variety of commercially available live yoghurt preparations as a widely-acceptable, but as yet unproven, adjunct to medical therapies. The recent UK report quoted [55] shows a significant effect of one specific commercially available live yoghurt product in preventing CDAD in a small subgroup of hospitalised patients. This measure could reasonably be combined with infection control measures and, possibly, consideration in deciding whether to prescribe acid-inhibiting drugs in preventing CDAD. What remains unknown is how nutritional status as well as medical comorbidity affects outcome in CDAD and further research on these issues as well as probiotic use and ideal antibiotic regimens is warranted.

- Commun Dis Intell. 2003;27 Suppl:S143-6. Non-antibiotic therapies for infectious diseases. Carson CF, Riley TV. Department of Microbiology, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, Western Australia.

Abstract. The emergence of multiple antibiotic resistant organisms in the general community is a potentially serious threat to public health. The emergence of antibiotic resistance has not yet prompted a radical revision of antibiotic utilisation. Instead it has prompted the development of additional antibiotics. Unfortunately, this does not relieve the underlying selection pressure that drives the development of resistance. A paradigm shift in the treatment of infectious disease is necessary to prevent antibiotics becoming obsolete and, where appropriate, alternatives to antibiotics ought to be considered. There are already several non-antibiotic approaches to the treatment and prevention of infection including probiotics, phages and phytomedicines. There is some evidence that probiotics such as Lactobacillus spp. or Saccharomyces boulardii are useful in the prevention and treatment of diarrhoea, including Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea that can be difficult to treat and recurs frequently. Bacteriophages have received renewed attention for the control of both staphylococcal and gastrointestinal infections. Phytomedicines that have been utilised in the treatment of infections include artesunate for malaria, tea tree oil for skin infections, honey for wound infections, mastic gum for Helicobacter pylori gastric ulcers and cranberry juice for urinary tract infections. Many infections may prove amenable to safe and effective treatment with non-antibiotics. - Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2000 Jun;13(3):215-219. Non-antibiotic therapy for Clostridium difficile infection. Banerjee S, Lamont JT. Division of Gastroenterology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Abstract Treatment of Clostridium difficile infection with metronidazole or vancomycin is successful in the majority of cases, but relapse occurs in 15% to 20% of patients, and in some the infection can remain chronic for months or years. The use of non-antibiotic therapies for this infection is theoretically attractive, as they would enable the normal colonic microflora to be reconstituted which is a requirement for permanent eradication of this pathogen. Over the past decade a number of non-antibiotic approaches to eliminate or neutralize C. difficile or its toxins have been proposed, including probiotic therapy with non-pathogenic microorganisms and several forms of immunotherapy. These alternative approaches are in their infancy, but initial reports appear to support efficacy against this stubborn infection.

Probiotics and S. boulardii Yeast Probiotics for C. diff.

The yeast probiotic S. boulardii is an effective choice for C. difficile diarrhea and antibiotic associated diarrhea

Probiotics and C. difficile Studies

- Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults and children, Joshue Z Goldenberg et al, 31 MAY 2013 The Cochrane Library.

- The search for a better treatment for recurrent Clostridium difficile disease: use of high-dose vancomycin combined with Saccharomyces boulardii. C M Surawicz 1, L V McFarland, R N Greenberg, M Rubin, R Fekety, M E Mulligan, R J Garcia, S Brandmarker, K Bowen, D Borjal, G W Elmer. Clin Infect Dis. 2000 Oct;31(4):1012-7.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11049785/ - Timely Use of Probiotics in Hospitalized Adults Prevents Clostridium difficile Infection: A Systematic Review With Meta-Regression Analysis. Shen NT et al. Gastroenterology. 2017 Jun;152(8):1889-190.

- Validating bifidobacterial species and subspecies identity in commercial probiotic products, Lewis ZT, Pediatr Res. 2016 Mar;79(3):445-52.

- Review article: Anti-inflammatory mechanisms of action of Saccharomyces boulardii. C. Pothoulakis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009 Oct 15; 30(8): 826–833.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2761627/ - A randomized placebo-controlled trial of Saccharomyces boulardii in combination with standard antibiotics for Clostridium difficile disease. McFarland LV, Surawicz CM, Greenberg RN, Fekety R, Elmer GW. JAMA. 1994 Jun 22-29;271(24):1913-8.

- A randomized placebo-controlled trial of Saccharomyces boulardii in combination with standard antibiotics for Clostridium difficile disease, McFarland LV, JAMA 1994 Jun 22-29; 271(24):1913-8.

- Saccharomyces boulardii inhibits Clostridium difficile toxin A binding and enterotoxicity in rat ileum. Pothoulakis et al, Gastroenterology. 1993 Apr;104(4):1108-15.

- Probiotics in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and Clostridium difficile infection. Hickson M. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2011 May; 4(3): 185–197.

- Saccharomyces boulardii Stimulates Intestinal Immunoglobulin A Immune Response to Clostridium difficile Toxin A in Mice. Qamar et al, Infect Immun. 2001 Apr; 69(4): 2762–2765.

- Saccharomyces boulardii protease inhibits Clostridium difficile toxin A, Chapter 14 – Probiotics 202 effects in the rat ileum. Castagliuolo et al. Infect Immun. 1996 Dec;64(12):5225-32.

- Review article: Anti-inflammatory mechanisms of action of Saccharomyces boulardii. Pothoulakis, C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009 Oct 15; 30(8): 826–833.

- Effect of biotherapeutics on cyclosporin-induced Clostridium difficile infection in mice. Kaur et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Apr;25(4):832-8.

- Lactobacillus acidophilus CL1285, Lactobacillus casei LBC80R, and Lactobacillus rhamnosus CLR2 (Bio-K+): Characterization, Manufacture, Mechanisms of Action, and Quality Control of a Specific Probiotic Combination for Primary Prevention of Clostridium difficile Infection. Auclair et al. Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 60, Issue suppl_2, 15 May 2015, Pages S135–S143.

- A framework for human microbiome research, The Human Microbiome Project Consortium, Nature 486, 215–221 (14 June 2012).

- Host-Pathogen Interactions: the seduction of molecular cross talk, J. Gut 2002;50:32.

- Recommendations for probiotic use – Floch et al, J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008 Jul.

- Treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile colitis: a narrative review. Roy J Hopkins and Robert B Wilson. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2018 Feb; 6(1): 21–28.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5806400/

Bacillus Spore Probiotic Studies for C. diff. and Other Gut Challenges

B. coagulans, B. clausii and B. subtillis probiotics seek out and fight gut pathogens including C. difficile that cause inflammation and diarrhea.

- Bacillus spore probiotics shine very brightly when it comes to C. difficile. They are highly targeted “true probiotics” that are used in Michelle’s recommended probiotic products including MegaSporeBiotic.

- B. coagulans therapy has shown to improve C. difficile colitis symptoms, reduce colon inflammation, provide better stool consistency and improve C. diff. outcomes3 as well as reduce recurring C. diff. after vancomycin treatment2.

- Bacillus clausii makes the antimicrobial compound clausin that directly inhibits C. difficile and other Gram-positive bacteria5.

- Bacillus clausii creates an enzyme that helps break apart C. difficile toxins, resulting in a strong protective effect against intestinal damage1.

- Bacillus subtilis HU58 produces over 12 targeted antimicrobial substances. B. subtilis effectively targets harmful gut bacteria, making it a potent and effective tool to rebalance gut flora.

- Bacillus subtilis enhances the immune system in elderly subjects as indicated by increased immunoglobulin A (IgA) levels7. IgA fights off invading organisms and is your body’s first line of defense.

Bacillus spore probiotics have been used safely for decades around the world. Also note that while scientific studies are important, it’s equally important that a food, supplement, probiotic or ingredient have a long history of safe and effective use in day to day clinical settings between real doctors and their patients.

Fortunately, there has been much research on Bacillus spores in general and on MegaSporeBiotic in particular. But just as important and valuable are the real-world effects that this and other products are having in people.

Michelle Moore’s methods in her book and recommended products are based heavily on real-world experience by consulting with medical professionals about what works with their patients, which is the approach of holistic or natural medicine in general. This approach is very different from mainstream medicine, which relies heavily on “proof” of safety and efficacy through the rigid paradigm of FDA drug approval, the universal use of “standard protocol” treatments and the dismissal and even attack on alternatives. Both mainstream and holistic medicine have overlap and usefulness, but they are also very different and usually provide very different results. This important topic is detailed in chapter 4 of Michelle’s book C. difficile Treatment & Remedies.

Bacillus Probiotic Targeted C. difficile and Immune Benefits

Bacillus Spore Probiotic and C. difficile Studies

- Secreted Compounds of the Probiotic Bacillus clausii Strain O/C Inhibit the Cytotoxic Effects Induced by Clostridium difficile and Bacillus cereus Toxins. Ripert G. et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016 Jun; 60(6): 3445–3454.

- Bacillus coagulans GBI-30, 6086 limits the recurrence of Clostridium difficile-Induced colitis following vancomycin withdrawal in mice. Fitzpatrick L, Small J, Greene W, Karpa K, Farmer S, Keller D. Gut Pathog. 2012; 4: 13.

- Bacillus Coagulans GBI-30 (BC30) improves indices of Clostridium difficile-Induced colitis in mice. Fitzpatrick L, Small J, Greene W, Karpa K, Keller D. Gut Pathog. 2011; 3: 16. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22014083/

- The use of bacterial spore formers as probiotics, FEMS Microbiology Reviews 29 (2005) 813–835

- Probiotics for Prevention of Clostridium difficile Infection. Mills J, Rao K, Young V. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2018 Jan; 34(1): 3–10.

- The safety of Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus indicus as food probiotics, Journal of Applied Microbiology ISSN 1364-5072

- Probiotic strain Bacillus subtilis CU1 stimulates immune system of elderly during common infectious disease period: a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study. Lefevre M, Racedo SM, Ripert G, et al. Immun Aging. 2015;12:24.

- The Intestinal Life Cycle of Bacillus subtilis and Close Relatives, JOURNAL OF BACTERIOLOGY, Apr. 2006, p. 2692–2700

- Pathogen elimination by probiotic Bacillus via signalling interference. Pipat P., Yue Z., Thuan N., Seth D. et el. Nature, 2018. Chapter 14 – Probiotics 201

- Oral spore-based probiotic supplementation was associated with reduced incidence of post-prandial dietary endotoxin, triglycerides, and disease risk biomarkers. Brian K McFarlin. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2017 August 15; 8(3): 117-126.

- Bacillus probiotics, Food Microbiology 28 (2011) 214e220

- Characterization of Bacillus Species Used for Oral Bacteriotherapy and Bacterioprophylaxis of Gastrointestinal Disorders, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 0099-2240/00/$04.0010, Dec. 2000, p. 5241–5247

- Efficacy of Bacillus clausii spores in the prevention of recurrent respiratory infections in children: a pilot study, Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management 2007:3(1) 13–17

- Bacillus Probiotics: Spore Germination in the Gastrointestinal Tract, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, May 2002, p. 2344–2352

- Bacillus subtilis antibiotics: structures, syntheses and specific functions, Molecular Microbiology (2005) 56(4), 845–857

- Immunostimulatory activity of Bacillus spores, FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 53 (2008) 195–203

- Effect of Bacillus subtilis spore administration on activation of macrophages and natural killer cells in mice, Veterinary Microbiology 60 1998 215–225

- The effect of Probiotic Bacillus subtilis HU58 on Immune function in Healthy Human, The Indian Practitioner q Vol.70 No.9. September 2017

- Use of Bacillus subtilis PXN21 spores for suppression of Clostridium difficile infection symptoms in a murine model. Claire Colenutt 1, Simon M Cutting. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2014 Sep;358(2):154-61.

- Recommendations for the adjuvant use of the poly-antibiotic–resistant probiotic Bacillus clausii (O/C, SIN, N/R, T) in acute, chronic, and antibiotic-associated diarrhea in children: consensus from Asian experts.Jo-Anne De Castro, Dhanasekhar Kesavelu, Keya Rani Lahiri, Nataruks Chaijitraruch et al. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines. 2020; 6: 21 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7583175/

Fill in the form below to get our C. diff. tips newsletter and your free report “10 Things You Need to Know to Overcome C. difficile”.

We value your Privacy. Your email will be kept strictly confidential & secured. See our

Fill in the form below to get our C. diff. tips newsletter and your free report “10 Things You Need to Know to Overcome C. difficile”.

We value your Privacy. Your email will be kept strictly confidential & secured. See our